Alpine Essays from The Roof of Europe

In the late 1980s I worked with the Swiss ecological charity Alp Action, founded by Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan and managed by my friend Marc Sursock. To further their high and just aims, I wrote some short essays with extensive quotes from various authors who knew the Alps for The Roof of Europe, a book about Alp Action published in 1990 by the Bellerive Foundation in Geneva. These essays describe the importance of the Alps in various works by Herman Hesse, Thomas Mann, J.M.W. Turner, Carl Jung, Nietzsche, and Percy Shelley.

Herman Hesse

Herman Hesse

Herman Hesse’s Glass Bead Game

The German novelist and 1946 Nobel Prize Winner Herman Hesse (1877—1962)

lived his entire life in the Alps, but was enraptured by the mystical East

(to which he never traveled). His pacifism and sublime art were central aspects

of his being, presented through astonishing creative forms. His primary spiritual

and literary instincts gripped his whole personality to such an extent that

all others were in abeyance, thus giving rise to works of divine perfection.

His great work The Glass Bead Game (1943) is about the Great Spirit and its descent into humanity, symbolized by the mountainous environment as the place of the death of the Master:

“The journey also led from fading summer deeper into autumn. About noon the last great climb began, over sweeping serpentines, through shining evergreen forests, past foaming mountain streams roaring between cliffs, over bridges and by solitary, massive walled farmhouses with tiny windows, into a stony, ever rougher and more austere world of mountains, amid whose bleakness and sobriety the flowering meadows bloomed like tiny paradises with doubled loveliness. Before him the little lake lay motionless, gray-green. Further off was a steep cliff, its sharp, jagged crest still in shadow, rearing sheer and cold into the thin, greenish, cool morning sky. But he could sense that the sun had already risen behind this crest; tiny splinters of its light glittered here and there on corners of rock. In a few minutes the sun would appear over the crenellations of the mountain and flood both lake and valley below with light. Now, even more strongly than during yesterday’s ride, he felt the ponderousness, the coolness and dignified strangeness of this mountain world, which does not meet men halfway, does not invite them, scarcely tolerates them. And it seemed to him strange and significant that his first step into the freedom of life in the world should have led him to this very place, to this silent and cold grandeur.”

Carl Gustav Jung

Carl Gustav Jung Jung and Mountain Symbolism

The great Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (1875—1961) lived and

practiced near the mountains in Zurich. He was the son of a clergyman and

one of his first formative experiences, described in his autobiography Memories,

Dreams and Reflections came while he went on a rare journey alone in

the Alps with his father. After boarding a steamship, the 17-year-old Jung

and his father arrived in Vitznau. Above the village towered a high mountain,

the Rigi, and a slanted cogwheel railway ran up to it.

“My father pressed a ticket in my hand and said, “You can ride up to the peak alone. I’ll stay here; it’s too expensive for the two of us. Be careful not to fall down anywhere.” With a tremendous puffing, the locomotive shook and rattled me up to the dizzy heights where ever-new abysses and panoramas opened out before my gaze. “Yes,” I thought, “this is it, my world, the real world, the secret, where there are no teachers, no schools, no unanswerable questions, where one can be without having to ask anything. This was the best and most precious gift my father had ever given me.”

The mountains remained sacred to Jung. He discovered that mountains and trees

are symbols of the personality and of the self. Christ, for example, is symbolized

as the mountain by St. Ambrose. Many years later, when Jung was visiting the

Pueblo Indians in the southwest of America, an old chief asked him. “Do

you not think that all life comes from the mountain?” According to the

symbolism Jung revered, the mountain contains “. . . every sort of knowledge

that is found in the world. There does not exist knowledge or understanding

or dream or thought or sagacity or opinion or delineation or wisdom or philosophy

or government or peace or courage outside of the mountain.”

Thomas Mann’s Magic Mountain

The 1929 Nobel Prize winning author Thomas Mann (1875—1955) located

his novel The Magic Mountain (1924) at a sanatorium above Davos,

the highest town in the Alps, which may have prefigured his later need to

escape from his native Germany to those neutral heights. Hans Castorp was

sent to recover from tuberculosis on the Magic Mountain:

“He sat there and looked abroad, at those mist-wreathed summits, at the carnival of snow, and blushed to be gaping thus from the breast work of material well-being. If it was uncanny up there in the magnificence of the mountains, in the deathly silence of the snows — and uncanny it assuredly was, to our son of civilization — this was equally true, that in these months and years he had already drunk deep of the uncanny, in spirit and in sense. So if we can speak of Hans Castorp’s feeling of kingship with the wild powers of the winter heights, it is in this sense, that despite his pious awe he felt these scenes to be a fitting theatre for the issue of his involved thoughts, a fitting stage for one to make who, scarcely knowing how, found it had developed upon him to take stock of himself, in reference to the rank and status of the manlike god."

"Nowhither, perhaps; these upper regions blended with a sky no less misty-white than they, and where the two came together, it was hard to tell. No summit, no ridge was visible, it was a haze and a nothing, toward which Hans Castorp strove; while behind him the world, the inhabited valley, fell away swiftly from view, and no sound mounted to his ears. In a twinkling he was a solitary, he was as lost as heart could wish, his loneliness was profound enough to awake the fear which is the first stage of valor. On all sides there was nothing to see, beyond small single flakes of snow, which came out of a white sky and sank to rest on the white earth.”

“Snow Storm: Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps” (Turner, 1812)

Turner’s Alpine Landscapes

The English landscape painter J.M.W Turner (1775—1851) is usually associated

with paintings of sunsets, sea battles and Lake District scenes, but he was

influenced profoundly by his trips to the Alps. He first went in 1802 and

executed hundreds of drawings and watercolors that were inspirational to his

later work.

One of his most famous paintings (above) is “Snow Storm: Hannibal and his army crossing the Alps” (1812). It is believed that during a particularly violent storm at Famley Hall, where he lived, Turner witnessed a storm which revealed to him the story of Hannibal’s struggle against the elements, made more vivid by memories of his own adventures in the Alps. Meanwhile, the storm roiled and swept and shafted out lightning, and Turner’s imagination worked at the head of an army of elephants crossing the rocky sweeps of the Alps.

Of the hanging of the paintings at the Royal Academy in 1812, the catalogue

said, “Turner is perhaps the first artist in the world in the brilliant

and powerful style peculiar to him; no man has ever thrown such masses of

color upon paper; and his finest works are from the noblest scenery in the

world. The Swiss Alps — Views of Mont Blanc — Chamourcy —

The Devil’s Bridge — The Great St. Bernard — The Mer de

Glace. Mountains mingling with clouds, and rich with all the effects of Storm

and Sunshine; Cataracts plunging into Invisible Depths; Lakes shining like

Blue Steel under the Alpine sun, clouded by forests hanging over the ice;

uplands covered with vines and olives, and solitary sweeps of splendid snow.”

Turner showed the magic and beauty of the Alps as well as their mythic origins,

a just combination for the romantic English sensitive lover of art.

Sherlock Holmes in the Alps

Of the many famous authors of detective stories to have lived in or written about

the Alps, none was more famous than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859—1930),

the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Doyle was a huge, burly man and a considerable

athlete, and he originally came to Davos for his wife’s health. Doyle pioneered

the new sport of Alpine skiing, Much to the amusement of the locals, he set

off with two Davos guides on virtually bare boards to cross the Alps to Arosa.

He completed his mission, difficult today even with the best equipment, although

he apparently finished the last three hundred meters on his bottom.

Doyle set a number of Sherlock Holmes stories in the Alps. In 1893, he was so tired of creating the signature intricate plots, which he considered inferior to his historical novels, that he decided to kill off his hero Holmes at the Reichenbach Falls. He wrote to his mother that after Reichenbach, “the gentleman vanishes, never, never to return.” Reichenbach was carefully chosen as the tomb for the great detective, who was to be finally outwitted by the diabolical Moriarty and the seductive Irene Adler, the only woman Holmes could not resist. Holmes met his apparent end when he disappeared in one of the dark caverns under the roaring waterfall.

The European public was stunned at Holmes' death: Londoners wore mourning bands. One lady started her letter to Conan Doyle;“You brute!” Doyle was under great pressure to write more Holmes stories, but it was ten years before a shift in family fortunes made him bring Holmes back to life (though not Irene) in The Return of Sherlock Holmes. He had first published a pre-Moriarty tale, The Hound of the Baskervilles. It seemed as though Holmes, the nature lover, survived the deadly duel with Moriarty due to his intricate knowledge of Alpine caves, the Reichenbach region and an arcane oriental defensive technique called Baritsu. After traveling to Tibet, Mecca and Khartoum, most certainly on various secret missions for the Foreign Office, Holmes suddenly reappeared at Baker Street, causing the usually implacable Watson to faint.

Today supposed relics of the fictional Holmes and Watson are not to be found at 221b Upper Baker Street, but rather in Lucerne, Switzerland, in a medieval castle where English and Swiss police, both despised by Holmes, present friendly seminars applying the great detective’s logic to modern crime.

Nietzsche (by Edvard Munch, 1906)

Nietzsche (by Edvard Munch, 1906)

Zarathustra and the Spiritual Quest

The philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900) is the exact opposite

of a doctrine. It cannot be pinned down or defined. It denounces the taming

of philosophy and science by the state: “the state — the place

where the slow suicide of us all is called life” (from The

New Idol). The underlying meaning of Zarathustra is perhaps this revolt

of Thought against History. To the myth of progress he opposes the myth of

the eternal return — the value of the Self which is in constant renewal,

having continually to create and surpass itself. Among Nietzsche’s distinguished

readers are to be found André Gide (“Je ne suis jarnais; je deviens.”),

Albert Camus, Paul Valery, André Malreaux and Georges Bataille; and

in Germany, Thomas Mann and Hermann Hesse. Both the latter devoted their energies

to combating Nazism and proclaimed their debt to Nietzsche. Although many

absurd and incorrect things have been said about Nietzsche’s political

philosophy and still more abour his madness, he was quite simply a victim

of syphilis and died like Maupassant, Heine and Baudelaire, from total paralysis.

In 1870, the twenty-six year old Nietzsche was appointed to a professorship at the University of Basel, where he taught for ten years. The four parts of Zarathustra, left incomplete, were written at Rappalo and Sils Maria in the Engadin in the summer of 1883, as well as in Nice. It took him about ten days to write each part. In Thus Spake Zarathustra, Nietzsche presented the concept of the “Overman” (unfortunately translated as the "Superman") whose function is to discover the meaning of life by raising himself above the animals and the all-too-human. Zarathustra withdraws to the solitude of the mountains, but feels the call to give humanity the benefit of his understanding through a process of repeated ascents and subsequent realizations. The mountains thus become a metaphor for the spiritual quest.

“When Zarathustra was thirty years old he left his home and the lake of his home and went into the mountains. Here he enjoyed his spirit and his solitude, and for ten years did not tire of it. But at last a change came over his heart, and one morning he rose with the dawn, stepped before the sun, and spoke to it thus:

“You great star, what would your happiness be had you not those for whom you shine?

“Behold I am weary of my wisdom, like a bee that has gathered too much honey; I need hands outstretched to receive it. I would give away and distribute it, until the wise among men find joy once again in their folly and the poor in their riches.

“For that I must descend to the depths, as you do in the evening, when you go behind the sea and still bring light to the underworld, you over-rich star.

“Behold, this cup wants to become empty again, and Zarathustra wants to become a man again.”

Thus Zarathustra began to go under. And Zarathustra descended alone from the mountains.”

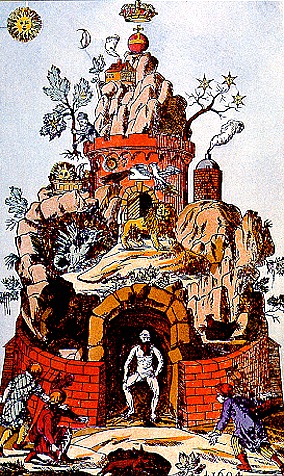

Alchemical Symbolism, Psychology & Art

Medieval philosophers attributed the word mountain to all metals. Alchemists

gave the same name to their vessels, kilns and metals. In a little work called

Lumen de Lumine or A New Magical Light Discovered and Communicated, published

in London in 1651, Eugenius Philaletes reveals a remarkable letter, presumably

from the Rosicrucian Order, “. . . concerning the Invisible Magical

Mountain And the Treasure therein Contained . . .” The mountain

is here taken as a symbol of the Soul of souls — the lnfinite.

Mountain symbolism appears in a text by Abdul Kasim quoted by C.G. Jung in Psychology and Alchemy. “. . . and one finds this Prime Matter (the unconscious, according to Jung) in a mountain enclosing all things created. . .” and “. . . there is no knowledge, no understanding, no dreams, no thought . . . which is not enclosed in it.”

Since the Renaissance, many artists have been inspired by mountains: among the most celebrated are Turner (one of his most celebrated works is “Hannibal crossing the Alps”), Da Vinci, Brueghel — whose wintry scenes of the Alps provide the background to skaters of his native Netherlands — the engraver Gustave Doré, and the painters Alexandre Calame and François Diday.

In the 19th century, two painters rebelled against the Romantic tradition of depicting idyllic, pastoral Alpine sceneries. Böcklin from Basle and the Italian Segantini (famous for his trilogy on birth, life and death) painted the Engadine and the intensity of the Alpine world in bold colours. Hodler painted the famous peaks — Mont Blanc, Jungfrau, Eiger, Dents du Midi — moving towards uncovering these elemental forces through abstraction.

The mountains have inspired a marriage between art and science. Modern scientific enquiries into mountain nature began with Rousseau, whose idealism spilled over into novels. Jung fused his mountain experience, the rational and irrational. Who cannot see the grandeur and purity of mountains, tinged with doubt, danger and uncertainty in Byron’s poetry and Tchaikovsky’s flamboyant, revolutionary Manfred? Amongst twentieth century authors, the Vaudois’ Ramuz is considered by the Swiss the greatest poet of nature since Rousseau. In a series of books, he depicts the homo alpinus (Alpine man) faced with overwhelming cosmic forces to which he must resign himself with patience and humility.

But through all the conflicts, dangers, and darkness, Alpine art reflects light on the peaks. As Goethe put it in a famous line in Uber allen Gipfeln ist Ruh: “On every summit peace reigns.”

Shelley’s Mont Blanc

Percy Byssche Shelley lived scarcely twenty-nine years (1792—1822),

yet captured a magic poetry which remains so beautiful and vibrant today that

one can scarcely imagine such a sublime being existing. His poetry is full

of mountains, seas and skies, of light and darkness, the seasons, and all

the elements of our being, as if Nature herself had written it with the creation

and its hopes newly cast around it. No poetry demonstrates his magic more

than this excerpt from“Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of

Chomouni.”

“Far, far above, piercing the infinite sky,

Mont Blanc appears — still, snowy, and serene.

Its subject mountains their unearthly forms

Pile around it, ice and rock; broad vales between

Of frozen foods, unfathomable deeps,

Blue as the overhanging heaven that spread

And wind among the accumulated steeps;

A desert peopled by storms alone,

Save when the eagle brings some hunter’s bone,

And the wolf tracks her there. How hideously

Its shapes are heaped around — rude, bare and high,

Ghastly, and scared, and riven! — Is this the scene

Where the old Earthquake-daemon taught her young

Ruin? Were these days their toys? Or did a sea

Of fire envelop once this silent snow? None can reply.

All seems eternal now. The wilderness has a mysterious tongue

Which teaches awful doubt — or faith so mild,

So solemn, so serene, that Man may be,

But for such faith, with Nature reconciles.

Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal

Large codes of fraud and woe; not understood

By all, hut which the wise, and great, and good

Interpret, or make felt, or deeply felt.”